There is an age-old tradition of military service being passed down through families. Throughout history,…

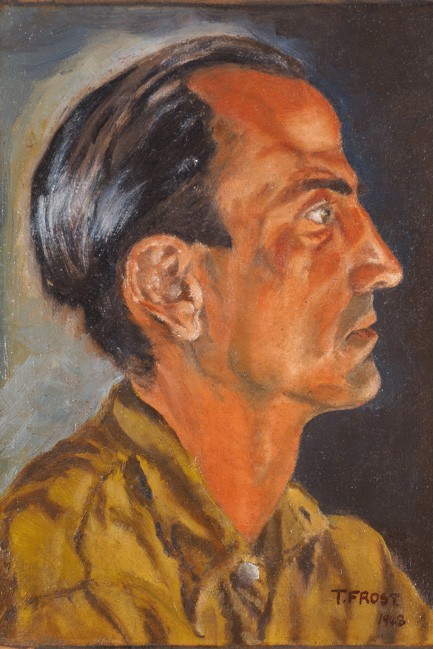

Collection Close Up: Portrait of Corporal Glyndwr James by Corporal Terry Frost

The landscape paintings made by Terry Frost are unlike any other representation of nature. A leading painter and printmaker of the twentieth century abstract movement, Frost uses an array of stripes, circles, and swirls in bold, vibrant colors to create his landscapes. His shapes do not concern themselves with rigidly copying nature but conveying its energy. His goal was not realism but representing “moments of truth” he observed in nature. For example, his painting entitled ‘Leeds Landscape’, held at the Tate Museum, is made of long black lines stretching across a tall canvas. They do not convey what the area looked like, but what it felt like to the artist. The portrait below does not follow these conventions; a realistic depiction, the painting is unlike Frost’s portfolio of pure abstraction. However, it is his painting, his name printed across the bottom corner, perhaps his very first. This partially explains the difference between his later paintings, his style had not yet developed. The differences run deeper though, the origins of the portrait setting it apart from all others. While most of his painting was done in the Cornish countryside resulting in his high energy landscapes, this portrait was created in a Nazi Prisoner of War Camp.

Who was Terry Frost?

Frost served in the Royal Armoured Corps during World War II, serving in France, Greece, and the Middle East. During the summer of 1941 he was stationed in Crete, part of the Allied attempt to block the German invasion of the island. The defense of the island was broken down by German paratroopers, sent in an unprecedented amount, and a fault in the Allied forces’ communications system leading to an Axis victory. In the midst of this defeat Frost was captured and sent to Stalag 383.

The camp was situated in a heavily forested valley in Hohenfels, Bavaria. Made up of hundreds of small huts, each accommodating 14 men, the whole camp held upwards of 8,000 prisoners of war. There was a mix of Allied troops, many British like Frost, but predominantly the camp held Polish prisoners of war. It was opened in 1939 for Allied NCOs but eventually held more ranks of soldiers; it would not be liberated until 1945.

It was in Stalag 383 that Frost began to paint, motivated by boredom and encouraged by a fellow prisoner and painter, Adrian Heath. Heath had studied art from the time he was 18 at Newlyn and the Slade School of Art before the war during which he joined the RAF. Serving as a tail gunner Heath, it was not long before Heath was captured; he would spend most of the war as a prisoner in Stalag 383. Here he met and became friends with Frost. While younger than Frost by 5 years, Heath was the one to encourage and teach Frost to paint. Art was a common pastime in prisoner of war camps as prisoners were often left with an abundance of free time.

Pass Time in Camp

While prisoners were forced to work in camps, the British were not as brutally used as their Polish and Soviet counterparts. British prisoners had a minimum level of treatment set out by Geneva Conventions, which allowed only non-officers to work, and the Red Cross monitored their treatment, often sending extra food for the prisoners. Thus, British prisoners of war had little to fill their days, making boredom their enemy. They fought off the monotony with many creative outlets, theater being a popular one in Stalag 383. The prisoners would put on performances for their fellows which even their German captors were reluctant to interfere with. There was a Talks and Debates Circle where all manner of topics were discussed, even modern art. Newspapers and magazines were made in the camp, some featuring cartoon panels. Entertainment was a necessity in a POW camp and the prisoners often had to stretch their creativity to occupy themselves during the daily drudgery. Frost’s initial foray into art was partly fueled by the need to escape boredom that most prisoners of war felt.

Facing the fear and boredom of prisoner of war life Frost first picked up his paintbrush. Unlike his later works of landscapes, Frost chose for his subject a fellow prisoner, Corporal Glyndwr James (his only other portraits are of himself, making this painting unique in his portfolio). Part of the Welch Regiment’s First Battalion James was also stationed in Crete in that summer of 1941 during which he too was captured. In this portrait he bears no mark of a soldier, stripped of his badges and uniform there is no evidence of his army service. He wears an unimposing prisoner uniform instead.

His appearance holds other marks of his time in Stalag- his eyes are hung with bags and faint scruff covers his upper lip and chin. Frost has carefully detailed the muscles and lines of James’ face, shown in profile. His neutral expression as he stares steadily straight ahead allows the tiny details Frost added to truly be seen. The black background is lightened from behind the figure, a halo of light around only the back of the head. It seems that the portrait was made in the dark with only a single light to illuminate the face for painting, perhaps made in the small huts at night.

Life After Camp

Glyndwr’s portrait is far removed from the abstract landscapes Frost would become famous for, but it remains true to his mission of revealing “moments of truth.” The strained lines making up James’ face exhibit the anxiety of prisoner of war life, yet the existence of the painting is proof there was leisure time, time when they could pour their focus away from those fears. Furthermore, the portrait’s history is a testament to the connections made between prisoners, curated during a time of shared peril often through the ability to create. Terry Frost’s style changed after his time in Stalag 383, advanced through learning under various abstract artists in art schools across England. He would go on to teach art himself, present his works in solo exhibitions, and even get knighted in 1998. He passed away in his beloved Newlyn, Cornwall in 2003, leaving a legacy of superb abstract art.